SABINAL — Nora Herrera recognized the faces.

They weren’t her children, but she used to joke with their parents that they were raised on her cooking. Truck drivers from Uvalde Estates would stop by Herrera’s food trailer, and they grew to love her fajitas, mollejas and potato-and-egg tacos — so much that they brought their families back on weekends.

Over the years, Nora’s Tacos moved into a permanent restaurant, and those families grew too. Herrera remembers serving pregnant women, who later were accompanied by infants, then by toddlers, then by grade-schoolers.

“When they come back, I tell them, ‘Hey, this kid is from Nora’s Tacos,’” Herrera said.

Around here, children tend to have lots of caretakers. About 11 miles of brush and farmland lie between Uvalde and Knippa along Highway 90, and about 10 more miles separate Knippa from Sabinal, but it really is all one place.

So when Herrera looked outside her restaurant Tuesday afternoon and saw all the cars pulled over by the roadside to let one emergency vehicle after another speed past, dread washed over her.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

If she didn’t know who the ambulances were coming for, she probably knew someone who did.

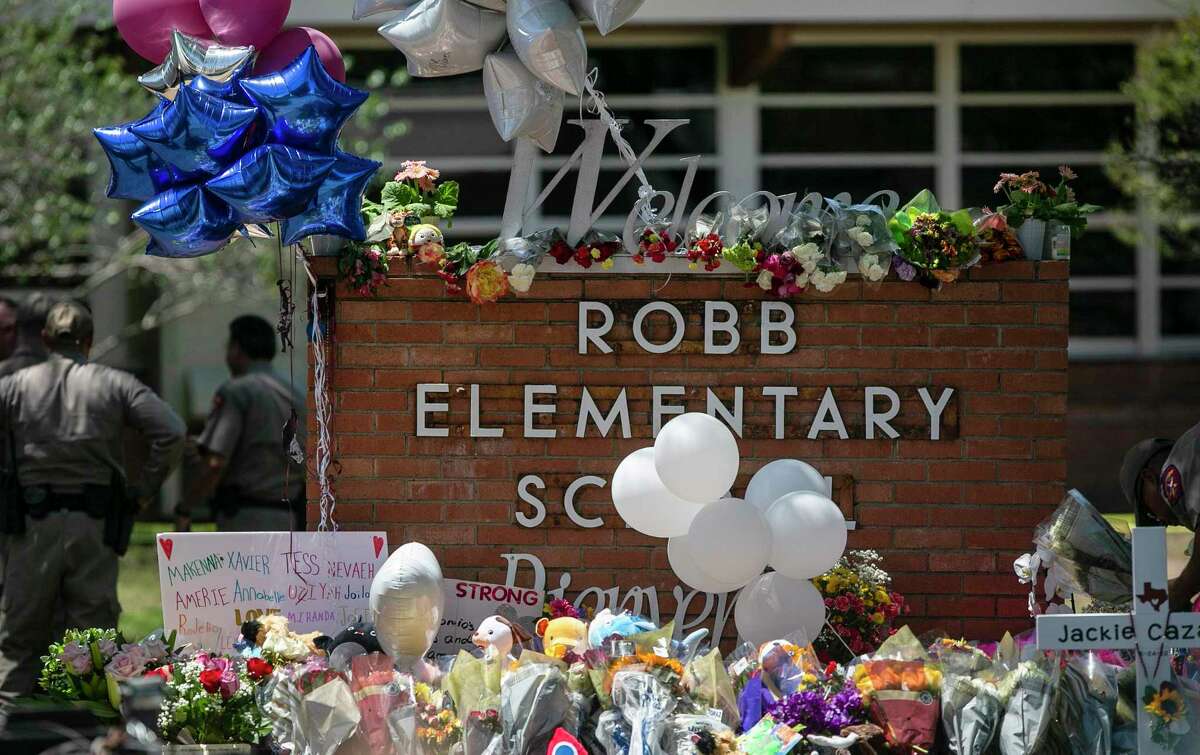

The next day, when photos of some of the 19 children killed at Robb Elementary began to pop up on social media? At Nora’s Tacos, on the east edge of Sabinal, a tragedy that already seemed unbearable hit even closer to home.

“My heart stopped,” Herrera said. “Those angels.”

“Some of those families are our usual customers,” said Herrera’s son, Raul Gomez. “Sadness. Distress. Anger. We feel all of that.”

They are far from alone. If they needed any reminder, all they had to do Wednesday was open the doors of the restaurant to a community that stretches from the Mexican border to the Hill Country and somehow still seems small.

“The people from all the towns, from Del Rio, from Concan, from Castroville, from Utopia, they all come in and say, ‘Nora, did you see what happened in Uvalde?’” Herrera said. “Everybody is crying. Everybody.”

What ‘Uvalde’ used to mean

To the rest of the world, “Uvalde” means something specific now, and it always will. It means unspeakable horror. It means grief and sadness and death, the same way “Columbine” and “Newtown” and “Parkland” do.

But to those of us who grew up in the little towns nearby, what “Uvalde” used to mean will never go away.

Uvalde is where brothers and cousins and aunts raised their families. Uvalde is where tubers and campers fill their coolers on the way to Garner State Park. Uvalde is where farmers order parts for their tractors.

Uvalde is where kids from all around the area ran track at the district meet and played each other in high school basketball at the Southwest Texas Junior College tournament and danced at the Purple Sage.

Uvalde is where we drove beat-up little pickups to the area’s closest operational movie theater, where we watched “The Fugitive” and “Speed” and took our time coming home, because even though we had no cell phones, our parents had no reason to worry.

Uvalde was where, just two summers ago, people brought face masks and lawn chairs to a beloved resident’s funeral service. This was before the COVID vaccine, which meant that seating inside Sacred Heart Catholic Church was limited. So hundreds of mourners – including some from my hometown of D’Hanis – filled an open lot just a few blocks from the main town square, and figured Uvalde couldn’t possibly feel more surreal than it did then.

‘Hope for a bright light’

In Knippa on Wednesday afternoon, just one vehicle sat parked outside the little businesses on Highway 90. It belonged to Jill Cox, who sat at a desk in the quiet offices of Ede & Company, Certified Public Accountants, with a throw pillow in her lap.

The phone wasn’t ringing. Nobody needed a bookkeeper now. But somebody had to be there, just in case.

“The world doesn’t stop, even though you want it to,” Cox said. “Come to work, and hope for a bright light.”

Cox was born in Uvalde, grew up in Carrizo Springs, lived in Edinburg for a while, and took the job in Knippa when she moved back to the area to raise her kids.

“You always feel like it’s safe here,” Cox said. “When we go places, to stock shows, you feel like if your kid misbehaves, somebody else is going to be watching. ‘Don’t make me tell your mother,’ you know?”

Like Herrera, Cox watched the police cars and ambulances zoom past her window on Tuesday afternoon. Then came the Facebook posts and the texts and the phone calls she couldn’t have imagined an hour earlier.

Her youngest daughter, Caitlyn Ledesma, a senior at Uvalde High School, said she was safe at the Sonic Drive-In, but said she couldn’t leave because the roads were blocked. Then Cox heard from a friend, a first-year teacher at Robb Elementary.

“She said, ‘I’m in a closet with my students, and they’re freaking out, and I don’t know what to do,’” Cox said. “I told her, just stay calm.”

But how could anyone do that? Just a day earlier, the seniors had walked through the halls of Robb in their caps and gowns, part of a Uvalde school tradition in which the graduating class is congratulated by elementary students. Now Ledesma, Cox’s daughter, couldn’t help thinking about the 9- and 10-year-olds whose faces had lit up as they reached up to high-five her.

And those kids’ parents? Cox has known some of them for what seems like forever. They were in Little League and 4H together.

“Now they have a child they’ll never hug again,” Cox said. “They have laundry in their house. When they go to fold a T-shirt, there’s not going to be a kid to go with it.”

Cox still has her children, and she is proud of how her youngest has coped with this week. Ledesma and her classmates have decided it would be inappropriate to hold a graduation ceremony or to celebrate what normally would be a milestone for any teenager. Instead, Wednesday morning, she and her friend delivered boxes from the Donut Palace to the local hospital that treated victims from Robb.

“She told me, ‘We’re forever in history now,’” Cox said of her daughter. “She said, ‘This is not what I wanted Uvalde to be known for. Now it’s going to be synonymous with a mass shooting of children.’”

‘It happened here’

Tuesday afternoon at D’Hanis High School, details of the Robb shooting were still drifting in when Todd Craft and Jose Martinez assembled their teams for practices. Craft’s baseball squad and Martinez’s softballers both won state championships in 2019, and both have a chance to win another in the next couple of weeks.

Craft, in his 26th year as the Cowboys’ head coach, started the session by sitting his players in the dugout and letting them talk. If they needed to discuss what had happened in Uvalde, just 35 miles down the road, they could. If they wanted to go home, that was fine. But they weren’t going to take the field until Craft made sure everybody was up for it.

Just then, a car pulled up to the baseball field, and a woman climbed out of the driver’s seat. She called out to her son, a junior on the team.

“She said she just wanted to hug him,” Craft said. “That was it. And she did.”

That did not make this mother in D’Hanis any different from mothers in Dallas or New York or Ukraine or in any of the other places where they watched the images from Robb Elementary in shock. Just as those little towns are connected to Uvalde by Highway 90, so too is the rest of the world by its shared grief.

Still, in the surrounding counties, the links were more personal. Martinez, the softball coach, grew up in Sabinal. When he first read the names of the shooting victims, nothing clicked. Then he realized that one of the students was the cousin of a D’Hanis player’s close friend. And that one of the slain teachers had a relative who Martinez often runs into at the Hondo H-E-B.

“You think you don’t know anybody,” Martinez said. “But it turns out somebody you know does.”

With that in mind, the girls on Martinez’s team asked him if they could wear maroon ribbons in honor of Uvalde when D’Hanis plays in the state semi-finals in Austin next week. They also plan to wear “Uvalde Strong” T-shirts during pregame warmups.

Craft said D’Hanis schools had extra security on Wednesday, and Martinez noticed it was on students’ minds all day.

“It was locked down, like it normally is,” Martinez said. “But you could tell, the kids came in, and they were double-checking the doors, being a little more protective. … You always think, ‘That’ll never happen here.’

“But it happened here.”

‘And you can’t do anything’

Back at Nora’s Tacos, Alejandra Salas tried not to think about it. She is Herrera’s sister, and she showed up for work in the kitchen on Wednesday.

She felt “a lot of things.” In some moments, despair. In others, gratitude.

Tuesday morning, Salas drove her 7-year-old daughter, Adelina, to a doctor’s appointment. Then, around 11 a.m., she dropped her off at the Robb Elementary cafeteria.

“She said, ‘Mommy, I’m scared. I don’t want to go,’” Salas said. “I said, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘I don’t know.’”

Less than an hour later, Salas got a phone call from a friend, informing her the school was locked down and there were reports of an active shooter. She raced back to the school.

It was hours before she found out Adelina was OK. Later, the girl told her mother she’d heard the “boom-boom-boom” of gunshots.

“You feel like you’re, how do you say it, impotente,” Salas said, using the Spanish word for powerless. “Your kids are right there. And you can’t do anything.”

This was not a feeling unique to one parent at one school.

The residents of Sabinal and other little towns along Highway 90 long have been part of Uvalde.

Now everyone is.

mfinger@express-news.net

Twitter: @mikefinge