Forget what you’ve been told. Cloud computing, software as a service (SaaS) and possibly even cybersecurity are bad investments. For the true believers, blockchain technology is poised, after years of hype, to trump all before it. Investors keen to understand the next chapter of the internet should forget the FAANGs, so this thinking goes, and focus instead on the world of smart contracts, decentralised networks and tokenisation.

Today, the internet is defined by its user-generated content, usability and dominance by a cluster of companies. It is sometimes referred to as Web 2.0, itself an evolution from the one-way information flows of the early internet.

Web 3.0, by contrast, has no agreed definition – in part because it is yet to fully arrive. But in the words of Fabio Chesini, an analyst at technology consultancy Gartner, it will come to represent the “further unbundling and reintermediation of the internet”. This involves breaking down barriers and an existing ecosystem that is dominated across much of the world by Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud, and moving everything onto public blockchains.

At its most basic, blockchain technology relies on networks of computers, which record and verify all the details of transactions and create blocks of data which are added to a chain of other blocks on a ledger. Each blockchain network is distinguished by its own set of rules, or protocols, although transactional transparency (and user privacy) are constants.

Unsurprisingly, its vanguard is evangelical. Solana Labs, a developer team behind one of the most hyped projects, explains: “Unlike an internet that’s dominated by a few major players, web3 [Solana’s term for Web 3.0] represents a distributed, peer-to-peer system that will run on a series of protocols and smart contracts that are maintained by a decentralized community.”

Perhaps this will lead to the democratisation of the internet, although the implications for those companies with near-omnipotence in digital services is debatable. Chesini is sceptical about what he terms an “illusion of exterminating central powers with blockchain”; maybe new titans will emerge, or big tech could adapt.

Crypto excess obscures a revolution

Serious investors may be missing the significance of what’s happening because of the bright lights and blaring noise given off by the crypto asset market. It’s not just about bitcoin. Crypto tokens such as Ethereum’s ether or Cardano’s Ada (named after Ada Byron Lovelace, a pioneer of computer mathematics), play an important role in the governance and economics of blockchain protocols. But on the fruit-machine-like exchanges there is little to distinguish cryptos underpinning genuinely exciting projects from the so-called “shit coins”.

Big names in blockchain admit the cowboy speculators and furious volatility in the market gives them an image problem. Blockchain is competitive but not on the basis of who has the best technology, says Dominic Williams, the founder of the Internet Computer, an open-source, general-purpose blockchain.

“[The crypto market] is like the height of the dotcom frenzy. Add in some very bad actors, because it’s an unregulated wild west, and amp it up by a hundred.

“The average person can’t understand the technology and invests on momentum,” continues Williams. “It’s like a casino and people invest on the hype cycle. It’s a dangerous place for investors.”

Williams is no stranger to this volatility. In May, the Internet Computer launched its own token, ICP, to enormous fanfare. After leaping to highs of $580 on its initial coin offering, it fell back dramatically. The coin now trades at around $50, which gives ICP a market capitalisation of around $8bn.

Cliff-edge price falls like this are the reason many sensible investors say no thank you to crypto assets. Still, it is worth trying to get a handle on the technology, because it will affect companies many own shares in.

Considering the future for some of the big technology themes investors have flocked to in recent years, such as SaaS and cloud computing, Williams is in little doubt: “Cloud computing is at its apogee. It’s still growing but it’s yesterday’s technology.”

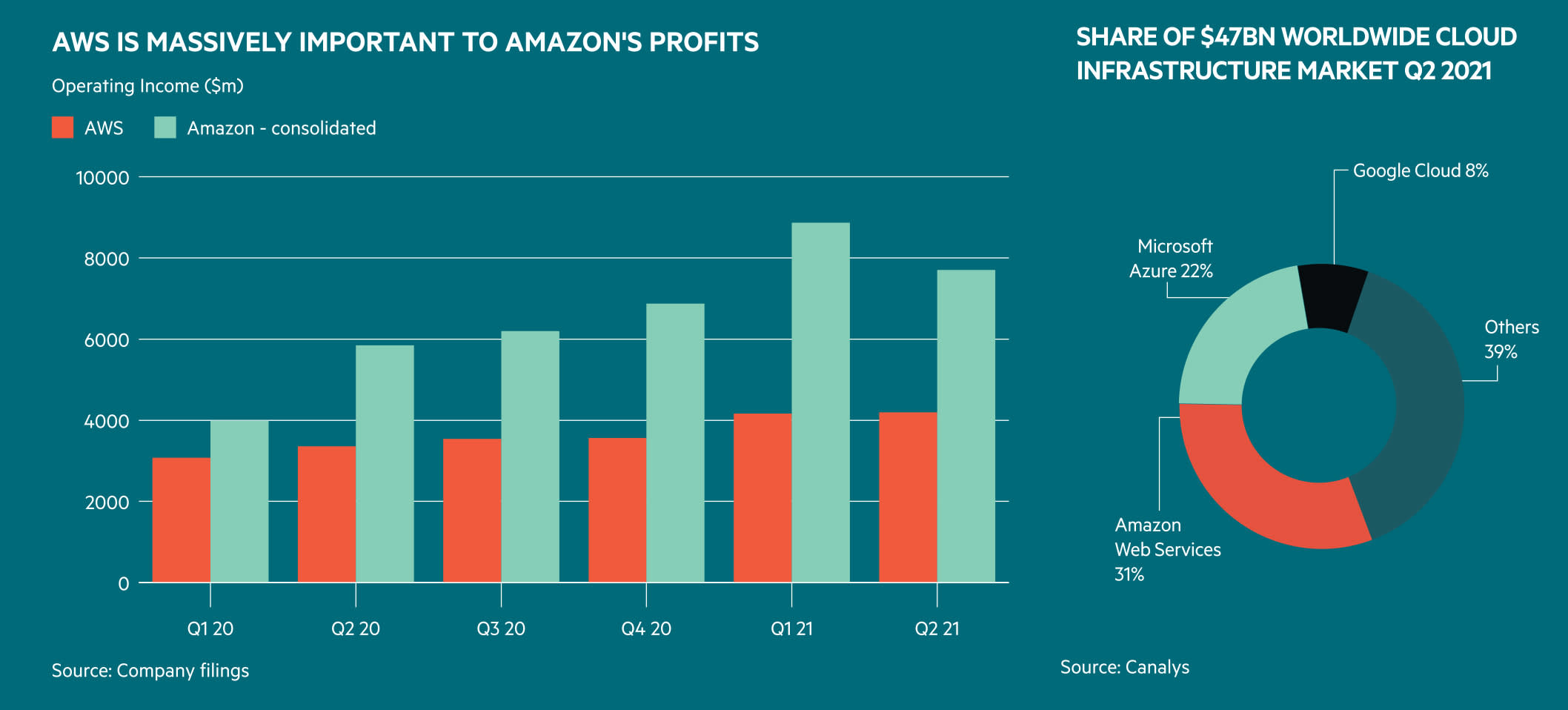

It’s not clear which of today’s tech titans are most at risk of disruption but they will be affected. The profit margins and cash flows of both Microsoft (US:MSFT) and Amazon (US:AMZN) have been massively boosted by their cloud computing divisions. These businesses offer diverse services and product innovations, so the question mark is not so much against their survival as the effect on earnings growth if the cloud stops raining cash.

For now, investment managers seem reasonably sanguine about the competitive threats to their holdings. “I worry less about decentralisation and blockchain disrupting companies and more about these get rich fast schemes diverting resources and people away from the big tech companies,” says Walter Price, portfolio manager of Allianz Technology Trust (ATT).

“To the extent that scarce developers go to these more dynamic companies, they don’t work on the projects the big companies need,” adds Price, noting that these same companies are ruthless in their efforts to add thousands of new employees a year “to continue to innovate”. Backed by bundles of cash and “monopoly annuities”, the incumbents can at least pay up for talent.

Still, there is no room for complacency. “There is definitely pricing pressure from the new entrants in their services,” says Price. “If you have an unsatisfactory consumer experience, you are vulnerable to disruption. I would say that the financial area is one with huge innovation and the potential for disruption as the merchants and consumers seek better deals.”

That chimes with the bold prediction Williams makes that in 10 years’ time, decentralised finance (DeFi) will be bigger than traditional finance. It’s all made possible by smart contracts, one of the most important blockchain innovations.

Smart contracts are computer protocols on the blockchain that can facilitate, verify and enforce negotiation and performance of a contract. Rather like using a human conveyancer when buying a house, the blockchain can store parts of a transaction until it is satisfied both parties meet their obligations and are ready to complete. This contrasts with platforms such as AWS or Azure, whose models rely on the centralised ownership of data.

The potential to offer customers decentralised banking services also explains why some developers are prepared to overlook the greater cost of storing data on a blockchain such as Ethereum (which issues the token ether) versus, say, AWS.

Competition between blockchains

Blockchains must verify transactions that take place and how they do this affects how fast, expensive and environmentally friendly they are to use. Costs are high on Ethereum because it relies on something called a proof-of-work (PoW) to mine ether, which has a high carbon footprint (although not as bad as bitcoin’s) because computers are needed to solve equations for the coins.

To reduce its carbon footprint, Ethereum is moving to a proof-of-stake (PoS) system, which is preferred by many new blockchains for its faster transaction times and lower environmental impact. Furthermore, PoS are central to the network effects new blockchains can use to disrupt large technology companies.

Investors buy governance tokens upfront, but they can stake these for rewards from network users, mainly interest in the form of more coins. The more useful projects that are built on the blockchain, the more valuable the coins become, so there is competition to have the cleanest and fastest performance. Projects with PoS like Solana (native token SOL), Cardano (ADA) and Internet Computer (ICP) have stirred excitement among developers of the decentralised applications (dApps) that will provide services on Web 3.0.

One ingredient of Solana’s secret sauce is its proof-of-history, which speeds up the work of verifying transactions.

Boasts of superiority are contentious, however, and Dominic Williams refutes any assertion that Solana is faster than the Internet Computer. “The hard thing about the blockchain industry is cutting through the chaff,” he says. “The Internet Computer finalises transaction updates in two seconds and query states in milliseconds.”

The Internet Computer can scale its capacity at a constant cost, says Williams, which is fundamental to its growth. Already, there are innovations in chat services taking place on the Internet Computer, which Williams believes could disrupt incumbents such as Snap’s (US:SNAP) Snapchat or Facebook’s (US:FB) WhatsApp.

DeFi adopters

The Solana Labs team gives the example of Pyth, a market data provider developed on the Solana blockchain which now counts more than 25 institutions on its network. Most of these users are digital trading businesses, but not just in crypto assets: the names of both Jane Street, one of the world’s largest market makers in listed securities, and high-frequency trader Hudson River Securities jump out.

For now, early adoption of smart contracts is being driven by the craze for non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which are a unique unit of data stored on the blockchain conferring rights of use to an asset. NFTs associated with basketball images, artworks and other digital memorabilia have traded for hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions of dollars.

Gartner is among several commentators that define the trend as the “Internet of Behaviours” (IoB). Anything that has a perceived value, such as a brand, can be tokenised and monetised. To Chesini, it’s like “marketing on steroids”, but with smart contracts it will be possible to enable tokenisation and sharing within social media apps on the blockchain. Innovations Facebook’s Instagram and WhatsApp businesses would struggle to keep up with.

Tether troubles

The applications for DeFi may be growing, but the field’s advocates remain cautious of associations with the broader crypto market. Cowboy finance on crypto exchanges has the potential to cause scandals, damage trust and set back the process of decentralisation.

The crypto lending market is an example of traditional financing activity being conducted on blockchain. But in the main, it’s pure leverage-funded speculation. Brokers and even individuals are able to convert fiat currency to so-called stablecoins and lend them to crypto traders, who offer some existing crypto assets as collateral. These traders then invest the borrowed stablecoins in more crypto assets.

Lenders get rates of interest many times higher than a traditional bank would offer. Why? Because the speculators are betting on the appreciation of crypto and the depreciation of fiat money. “Who cares [about paying] 10 per cent interest if the appreciation of the crypto is 10 or 20 times?” asks Chesini.

Volatility in the underlying markets and zero regulation of trading and margin calls is bad enough, but there is another enormous problem. This lending model is completely undermined by the questionable legitimacy of so-called stablecoins that fiat deposits are converted to.

Stablecoins are a mechanism for maintaining the value of digital assets without having to offload into fiat currencies, pay costly spreads and deal with long transaction verification times. Names such as US Dollar Coin (USDC) and US Dollar Tether (USDT) are supposedly pegged to the value of the global reserve currency.

Rather than trade two very volatile crypto assets, conducting one half of transactions in stablecoins aids price discovery and helps reduce spreads. Of course, stablecoins must be able to genuinely back up their value with real assets, and on this score tether is controversial.

Last week, a story in Bloomberg Businessweek detailed how the stablecoin is not backing a one-to-one USD valuation with safe assets, which would include actual hard currency, short-dated Treasury Bills and money market instruments. Instead, it has been buying the lower-quality commercial paper of Chinese companies, and – in a further twist – includes receivables from crypto-backed loans to crypto exchanges in its reserves.

Greater oversight may be inevitable, especially given the high interest rates offered for stablecoin deposits are inducement to funnel liquidity from the centralised financial system anyway. Regulation of stablecoins is something Chesini would welcome, although central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) might make them obsolete in any case.

If CBDCs get off the ground, it would provide a reliable stable digital asset and liquidity on public blockchains could be managed. That may seem anathema to the idea of decentralisation, but it could also help the maturation of DeFi, as focus shifts from speculation to real companies offering products and services on blockchain.

Further powerful disruption afoot

Fallout from the tether scandal could hurt crypto speculators but in the long run getting that house in order will be good for the blockchain industry and Chesini believes that “DeFi protocols are here to stay for sure”.

Nor should investors forget the regulatory and antitrust scrutiny and frequent scandals that beset the tech world’s incumbents. Facebook especially has attracted negative headlines, from its role in the Cambridge Analytica affair to recent allegations that it misled investors over managing potentially harmful content on its platform.

Along with its reputational problems, Facebook looks vulnerable to the rise of decentralisation, in the eyes of blockchain proponents. “The Facebook of the future will be very different, and it won’t be Facebook,” says Williams. “The WhatsApp of the future will be very different and it won’t be WhatsApp.”

One project built on the Internet Computer that Williams is excited about is OpenChat. The prototype is less than a year old, is awaiting features such as friendly domain names to be supported on the Internet Computer blockchain and isn’t yet fully decentralised. Still, Williams boldly predicts it will pass one million users within the next 12 months.

OpenChat is not run or owned by a company and its developers plan to decentralise it fully, using what they refer to as a “service nervous system”. Thereafter, developers will relinquish their ability to update it directly and the service will run as an extension of the blockchain.

Their reward will be ICP coins but simultaneously, a single clearing price auction – in which all tokens will be sold at the same price – will take place. This will give investors in the network an opportunity to buy the chance to vote on development projects in OpenChat. Another tranche of ICP will be held within the service nervous system to reward users.

The idea is that users will become advocates for the service, creating a network effect. The more activity on OpenChat, the more users it attracts. The more users, the more people will want to develop on it, and the better its features become. Such an ecosystem arguably offers the best opportunities for monetising themes such as the IoB.

“In the future, social media will be owned by users and users will be part of the team,” says Williams, who expects investment to pour into OpenChat decentralising in the coming years. Another exciting prospect is the opportunity for any developer with a good idea to be supported by the Internet Computer network nervous system and replicate the model.

There’s also a significant threat to the megacap holdings many investors own. Powerful network effects are what you need to take on big tech, says Williams. “That’s their moat.”