In October, Sarah Monson learned that Facebook was changing its name to Meta and shifting its focus to something called the metaverse, an immersive virtual world that did not yet exist, but the company said would one day take over the internet. Monson, a 44-year-old commercial writer and mother who recently moved to Hawaii, found the news disturbing.

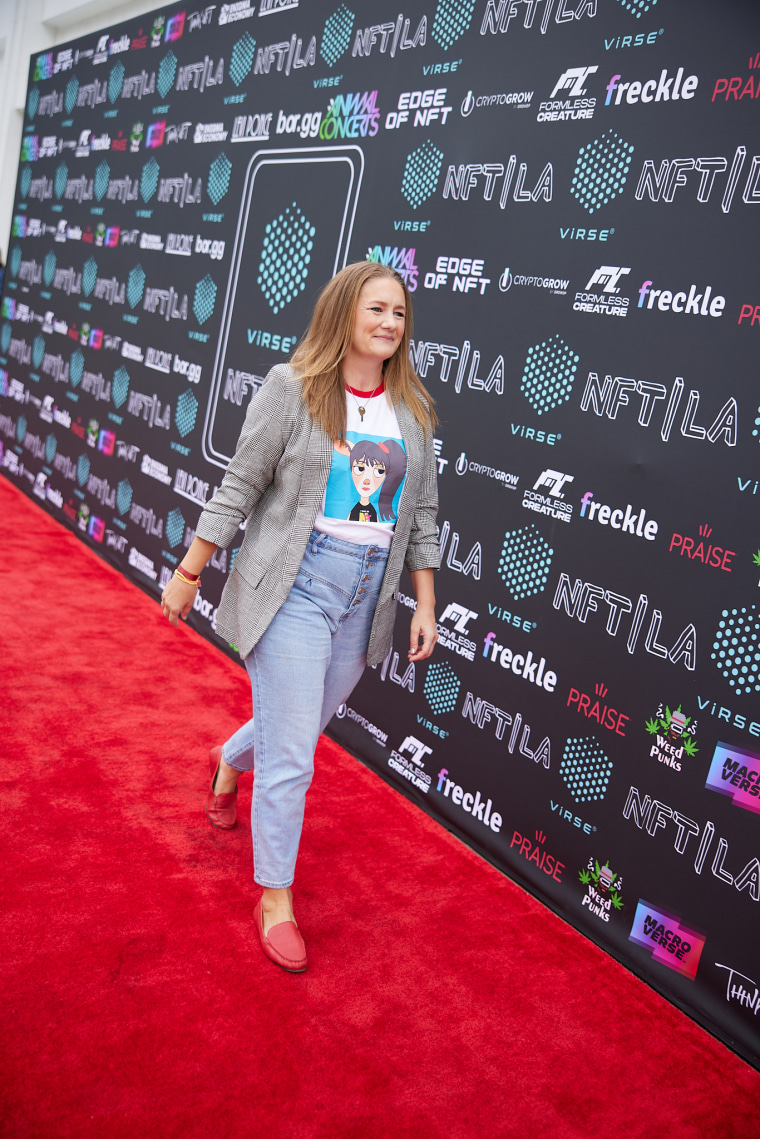

“I was like, oh my God, we are all going to be dragged into this creepy metaverse by Mark Zuckerberg, whether we like it or not, and have no say in it,” she said during an interview last week at NFT LA, a cryptocurrency conference in downtown Los Angeles.

Monson thought her 6-year-old daughter would encounter some version of the metaverse in the future and she wanted to be prepared. She decided the best thing to do was learn about the technologies that many proponents of the metaverse said would underpin it, including cryptocurrencies and NFTs, or nonfungible tokens.

“My whole point was, I want to educate myself,” Monson said. She also didn’t want to miss out on what was looking to her like another major tech boom. “I lived in Seattle during the dot com bubble and I had no voice or power to do anything,” she said.

Tune in to “Nightly News with Lester Holt” at 6:30 p.m. ET/5:30 p.m. CT for more of our coverage on crypto mothers.

Monson first began investing in crypto several years ago. But she spent the past five months diving into the market headfirst, listening to NFT podcasts, joining Discord servers, and connecting with other mothers on Twitter. She is now getting ready to launch her first NFT art collection, which she dubbed The Latchkey Kids, a reference to members of her generation born in the 1970s and ’80s. On the second day of NFT LA, she wore a face mask and T-shirt printed with the colorful cartoon goats she helped design for the project.

While younger, male Americans are more likely to say they have heard a lot about cryptocurrencies, a small but growing number of mothers, like Monson, are getting into the industry. For them, the stakes of investing in crypto can be higher. Most of the six mothers interviewed for this article said that they hoped crypto and NFTs would meaningfully change the financial security of their families for generations to come. They said they felt their perspective was different from that of the “crypto bros” often associated with the market.

“With more and more parents entering this space, we have a different mindset,” said Olayinka Odeniran, the founder of the Black Women Blockchain Council, an organization that supports Black women pursuing careers in the blockchain and fintech industries, who has a 12-year-old daughter. “Our approach is different from the single guys or girls who are solely here just to invest. We’re here really because we want to leave something for our family and we want them to be able to participate in our space.”

Odeniran and other mothers like her represent a minority of the crypto industry. Only 13 percent of American women in their 30s and 40s say they have invested in, traded or used cryptocurrencies, compared to 43 percent of men in their late teens and 20s, according to a Pew Research Center study published in November. Overall, twice as many men invest in crypto as women, a CNBC survey found.

The lack of women is so pronounced that it is often the subject of jokes. During the conference Monson attended, comedian Kristin Key mused on stage that perhaps NFT stood for “no females today.” (The audience didn’t laugh.)

But now, amid another bull market, a new wave of female-themed organizations have emerged that say they want to encourage more women to participate in crypto.

Deana Burke, a mother of two kids under age 5 and the co-founder of Boys Club, a crypto collective designed for women and nonbinary people, said there is more excitement about entering the industry among women than when she first joined a few years ago.

“I couldn’t get anyone to care,” said Burke. “But there’s now this ambient curiosity.”

Maternal branding

One of the most well-known “Crypto Moms” is Securities and Exchange Commissioner Hester Pierce. She was given the nickname by members of the crypto community, who often view her as an ally for their industry. Pierce said she mostly doesn’t mind being called a mother, even though she doesn’t actually have any biological children. But she also thinks her role shouldn’t be thought of as a parental one.

“I think it’s somewhat bad for a government official to be viewed in parental terms, because my philosophy for regulation is, look, this country is built on liberty and people making their own decisions,” she said. “I am certainly old enough to be a lot of these crypto people’s mothers, so from that perspective, it’s not too crazy either.”

Pierce isn’t the only person being referred to as a crypto mother. Brenda Gentry, a full-time crypto trader based in San Antonio, has branded herself online as “MsCryptoMom.” Her tagline: “Mother knows best.”

Gentry, 46, grew up in Kenya and previously worked as a mortgage underwriter for USAA, a financial services firm for members and veterans of the U.S. military. She quit in October, after she and her husband calculated that their retirement accounts would be worth around $400,000 or $500,000 if they continued working for the next 20 years, around the same amount Gentry said she had already made through crypto trading. Gentry said she is excited about the financial opportunities presented by crypto, but also aware of the risks involved.

“Sometimes, I see these young kids on Twitter saying, ‘I made so much on this NFT and I’m leaving my job,’ and I’m like, what?” Gentry said. “They forget that we have bad markets. You know, you got to think about that, too.”

Gentry said she protects herself by only investing in crypto projects that disclose the real names of the people behind them. She believes investment opportunities in the space are more likely to be scams if they are run by anonymous founders.

“I would not invest money if I don’t know who the team is. If I don’t know, if they are anonymous, I walk away. The only one that is anonymous is Satoshi,” Gentry said, referring to the creator of bitcoin, whose true identity remains unknown.

Seeking opportunities

Brenda Cataldo, a realtor and mother of five living in Palm Bay, Florida, said she sees crypto as a rare chance to build wealth for her family and greater community.

“If I’m able to make money, I’m able to help everybody else around me. I don’t think that’s a bad thing,” she said. “If you don’t take care of yourself, how can you take care of anyone else?”

Cataldo has invested in cryptocurrencies for a few years. But she began learning about NFTs on TikTok last fall. She is now getting ready to launch her own NFT collection called Luxe Ladies, which was modeled after her mother, who immigrated to the U.S. from the Philippines. She said 20 percent of the proceeds will go toward supporting foster children.

“I just think how lucky and blessed I was to have a mom that was such an advocate for me,” she said. “I want to give a little back to kids who don’t have that.”

Other mothers interviewed also said they view crypto as an avenue to raise money for charitable causes. Gentry said she and her husband have run a nonprofit supporting poor families in her native Kenya for years, but the extra money from trading cryptocurrencies has made a major difference.

“When my parents went back to Kenya in January, instead of helping the 20 or 30 people that we usually do, they could help 200 people,” she said. “So it’s not just generational wealth for my grandkids, my children’s kids that they haven’t even had yet, but it’s also for other other families.”

But Shailee Adinolfi, a mother and the director of strategic sales and accounts at the blockchain software company Consensys, warned that it’s currently not necessarily easy for people to transfer the money they earn from cryptocurrencies to their families or other organizations.

“What if you want to pass crypto down to your kids? There aren’t shared accounts,” she said. “We need to think about all kinds of people and how they interact with systems and not just develop them for the same group of people that are usually coding.”

Monson said she wants to convince more mothers like her to get involved with NFT art collections. But she said many of them worry about the environmental impact of bitcoin and how much electricity it uses.

Burke noted that there are a number of newer blockchain technologies already in use that are designed to consume fewer resources. She said there are plenty of people in crypto who want to address the harm being done to the environment, rather than contribute to it.

“The world that I’m part of in web3 and crypto is very, very, very climate-conscious and is actively working towards improving the situation,” she said.

Monson said she hopes that the industry will continue to evolve. For now, she plans to keep exploring what the crypto world could mean for her and her family’s future.

“I love my job and I love what I do, but I’m more than just a mom, and I feel like so many other moms, we need more,” she said. “This is a thrilling new life change.”