Note: This is the second part of a two-part series exploring the risks involved in contact sports and the dangers of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Click here for part one.

Many have heard about the lawsuit against the NFL involving former players who killed themselves and were diagnosed with CTE. But fewer people know that former ice hockey players are suffering the same way.

Let’s paint the picture of Rick Rypien, a former NHL player who played six seasons for the Vancouver Canucks.

Rypien, whom the New York Times described as “scrappy” and the “best pound-for-pound fighter in the NHL,” was only 5-feet-11-inches and 190 lbs. Even though he was far smaller than the average hockey player, he was an enforcer on the ice, and it earned him a $1.1 million contract in 2009.

Rypien died by suicide in 2011 and was later diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Now imagine former Quinnipiac men’s ice hockey captain Neil Breen’s reaction reading that news. He’s a player with a very similar archetype — 5 feet, 9 inches and 190 lbs during his junior hockey days — a tendency to fight and overwhelming CTE symptoms.

While one can’t be officially diagnosed with CTE until they’re dead and their brain can be operated upon, Breen has checked almost every box.

“Pretty bad anxiety on the regular, pretty uncontrollable,” Breen said. “My temper is violent … I have days where I can’t even leave the house. I get this sense of extreme anxiety that’s hard to explain.”

Breen, 43, speaks in a bit of a haze. If asked a question, you will probably get more than one answer — Breen put it best when he shared that he “talked in pieces.” Brain injuries, like concussions, can affect communication to the point where regular, daily actions don’t feel the same. So when Breen connected with former Team USA bobsledder William Person, a connection that Breen said “saved my life and refocused my path,” it was a feeling both knew all too well.

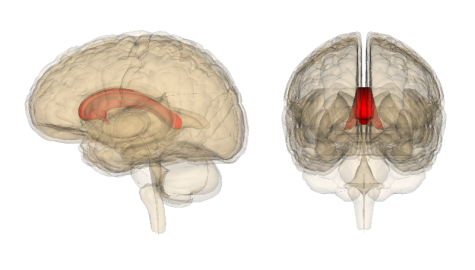

Bobsledding and skeleton leave athletes vulnerable to a phenomenon referred to as “sled head,” a slang term for what scientists call a stretch injury. While riding in a bobsled traveling close to 90 mph, the force applied to a rider’s brain causes a wave to move through the brain and cause damage. Stretch injuries corrode the corpus callosum, the nerve bundle that connects the two hemispheres of the brain.

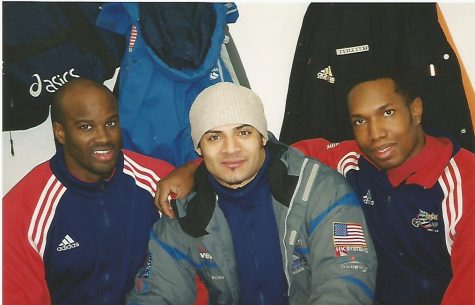

Person, 51, is currently suing USA Bobsledding and Skeleton for allegedly not disclosing information about the long-term dangers of the sport, particularly with head damage. The New York Times picked up the story, which is how Breen and Person first started talking. Their relationship is what led Person to become a vocal proponent of concussion awareness outside of his ongoing legal situation.

“Breen gave me the courage and the permission to move forward and bring it to the spotlight,” Person said. “Before I filed that lawsuit, I would hide. I didn’t want my name talked about, I didn’t want to discuss it, I didn’t. I was very, very, very low-key, hoping that maybe I’m just gonna die in my sleep tonight. And maybe it’ll be just over.”

Person started as a track athlete, running sub-4.3 40-yard dashes and performing in the long jump. He had no inspiration to bobsled before trying out in Chula Vista, California, for the 2002 Summer Olympics. After setting a new record at the event, Person was offered $50,000 for three months of competition.

“I gave him an educated answer. I said, ‘Well, if it’s a fair price, I’ll do it,’” Person said. “But in the back of my mind, I’m thinking, ‘50 grand for three months, sign me up.’ And that’s how I got started.”

That started a ride that would span nine years of intense competition. Bobsledding was a needed change-of-pace for Person, who enjoyed the new adventure. But between the crashes and the sharp turns came repeated blows to the head that plague him even now. Whether it was a “cloudiness” or “getting your bell rung,” it was just par for the course as a bobsledder.

“We didn’t have doctors out there. It was like, we slide, you crash, you just go back to the (top) — if you didn’t break an arm or a leg — you just went back to the top and did it again, that was your job,” Person said.

Person knows he’s not the only one suffering from the effects — it’s exactly what he talked to Breen about — and that’s what drove him to file the lawsuit. It’s about saving those suffering before it’s too late.

People read about athlete suicides in the news all the time. For Person, some of those athletes like Steven Holcomb, who overdosed and died in 2018 after fighting depression for years, were friends. Scientists did not find CTE when they inspected Holcomb’s brain.

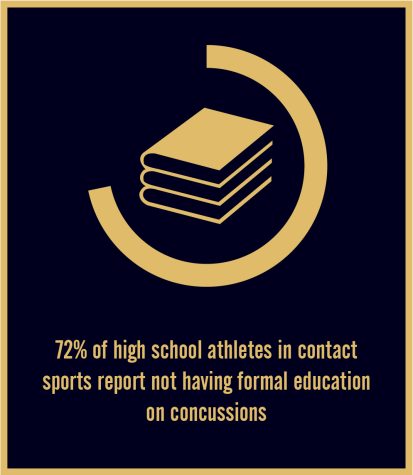

The topic of concussions and head trauma may linger in the spotlight as pro athletes call attention to it, but people like Breen never knew about this growing up. Most American hockey players start on the youth USA level, which requires a waiver to participate in.

The language used in a USA youth hockey waiver is tough to follow. CTE or long-term head trauma is never mentioned in the waiver. There’s bodily injury, paralysis, death, but there’s little mention of potential damages decades in the future. It is alluded to under the umbrella of ”damages which may arise therefrom and that (the signees) have full knowledge of said risks.”

Say that line three times fast. But that’s contract talk for parents signing their kids up for a contact sport they likely don’t completely understand. And why think too hard about it? Football is the only sport that causes severe head trauma, right?

The fear of brain damage has contributed to a decrease in football participants — a 2018 study by the University of California-Berkeley showed that a single season of high school football could change the structure of the teenage brain.

Meanwhile, the number of U.S. hockey players has almost tripled since 1990, according to a 2020 ESPN study. Signing your kid up to play is commonplace, something people don’t think twice about. Few think that signing their kid to play hockey or bobsled could lead them to severe mental illness brought on by repeated head trauma.

“In my opinion, (the waiver) should include the risk that you could heighten your chance for CTE from repetitive head trauma,” said Dr. Robert Cantu, medical director of the Concussion Legacy Foundation.

If Person had known the risk of bobsledding, he said he would have done things quite differently.

“That (first race) would have not happened,” Person said. “I would have not taken one trip. And then, we wouldn’t be having this conversation if I could go back.”

The real stories of people who are struggling with CTE symptoms are powerful, and there are a lot of them. But real stories told by actors is what helped accelerate the conversation even more.

The film “Concussion,” starring Will Smith, follows the real-life story of Dr. Bennet Omalu. He tried to bring to light the recent suicides and deaths of former NFL players, all of whom were posthumously diagnosed with CTE.

The abbreviation “CTE” is mentioned 10 times in the movie, and was referred to as “chronic traumatic encephalopathy” once. The word “concussion” is said 20 times.

Herein lies the confusion between concussions and CTE. Although the film did not mistakenly mix the two afflictions, their proximity in the world of athletic neuroscience has created confusion. Quinnipiac Medical Director David Wang, who has led field studies surrounding concussions and CTE, has tried to separate the two in the minds of the public.

“The movie is a great story, but it’s got the wrong title!” Wang said. “A concussion is a marker for somebody who gets hit in the head, it’s not a marker for who gets CTE.

“CTE is cumulative. We have these two tracks going: We have this concussion world, and we have the CTE world. And somehow, because of the way things are, people have melded them together.”

The flow of studies from medical professionals and high-profile media attention like “Concussion” have brought attention to these issues, but sometimes new information can cause some head-scratching. While concussions and CTE are often found in conjunction, studies that have tried to pinpoint causation between the two have been inconclusive.

In a study published by Current Pain and Headache Reports, only 84% of 92 participants found to have had CTE had a reported concussion history.

The average number of concussions reported in the same group of subjects was 17, suggesting that CTE is associated with multiple concussions. However, the remaining 16% of the group were found to have had CTE without a concussion history, possibly due to non-reporting.

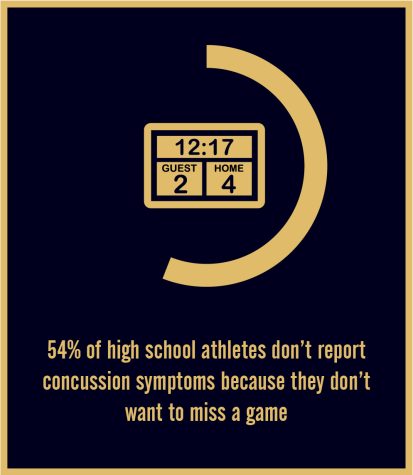

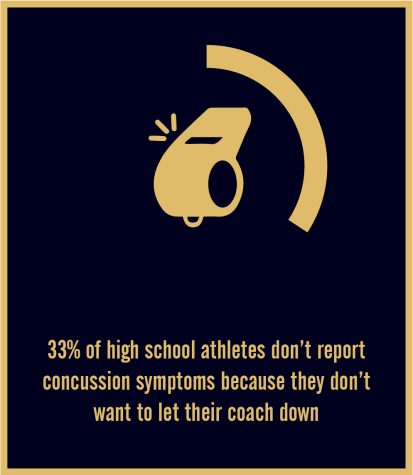

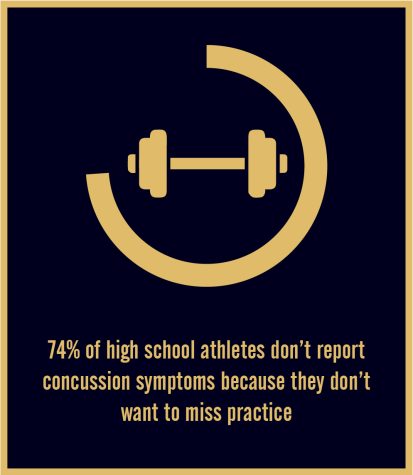

Athletes failing to report or recognize their injuries creates an additional variable that has prevented scientists from finding a conclusive answer about how many concussions lead to CTE, or how they are directly linked.

With no concrete resolution and increased awareness on how contact sports affect the brain, high school and youth sports entered the crosshairs.

“Every parent is starting to think that a concussion equals CTE, and now we have massive confusion, and then we have hysteria,” Wang said.

On the surface, there are answers to the issue of CTE. Organizations like the Concussion Legacy Foundation and efforts from doctors like Wang have saved lives.

But the testimonies from those who have suffered through wars with their mental health tell a different story, and the scientific question marks only make their lives more confusing.

As a former hockey player at Quinnipiac, Breen was the ultimate “bad boy.” He played a tough brand of hockey and wasn’t afraid of making a hit or getting in a fight with anybody. He’s described times where he was knocked unconscious or has taken slapshots to the face, and there were few hurdles to clear in order for him to be back in the game.

Being allowed to play while concussed and banged up led to Breen’s current mental state, which has steadily improved over recent months. But there is still a constant roadblock that he can’t get past. He’s tried so many possible solutions, from abstract medical treatment to prescriptions to self-medication of marijuana and psychedelic mushrooms. None of them have worked.

Growing increasingly frustrated with the lack of solutions to his mental health problems, he reached out to his alma mater in search of help. He didn’t know how to feel about his illness, or who was accountable.

In an email to the Dean of the Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine Phil Boiselle, Breen offered his own body for a proposed Quinnipiac-run CTE project after explaining his mental health struggles.

“Let’s solve this problem together and change the sporting world … I took a great deal of trauma during my 4 years at Quinnipiac,” Breen wrote. “I’m not looking for anything but help. I know that our research can save many lives.

“I may never have gone to QU had I not been talented at the puck. But I gave my all, sacrificed everything to lead our boys, ours and your school to new athletic heights.”

Boiselle responded the next day, saying that Quinnipiac is “not currently equipped to do the types of multidisciplinary, multi-center studies that are necessary to advance the diagnosis and treatment of CTE.” He said that he wanted to be “helpful” and referred Breen to the Concussion Legacy Foundation’s website. Associate Vice President for Public Relations John Morgan had nothing to add when contacted for comment by The Chronicle.

However, that is a route Breen’s all too familiar with. He’s met with neuroscientists, including the CLF, and hasn’t found an answer. The email was yet another reminder of the mountain in his way of recovery. And when that mountain was partially built during his time at Quinnipiac, it added an avalanche of frustration.

“I feel like Quinnipiac is responsible for the way I’m feeling right now. I mean, I don’t. I mean, should I?” Breen said.

Even though Breen has had symptoms for several years, he still doesn’t know who to blame, where to turn, who to ask for help. No one does.

“If you played college hockey, you probably played Bantam,” Wang said. “You played high school and everything else, maybe it was cumulative with that, too … I think it’d be very hard to assign responsibility to one particular sliver of time.”

Breen and Person have seen their lives become intertwined with CTE to the point where the two can’t be separated. Breen has had suicidal thoughts. Person set up a “non-suicide pact” with his teammates as a way for them all to look out for each other, but that doesn’t always work. The cycle continues. The decades-old cold war has stayed on its course.

Despite Breen and Person’s efforts through lawsuits, business ideas and social media interactions, a mountain stands before them. The base of the mountain is multiple centuries’ worth of toxic masculinity, hardheadedness and muscular culture that defined American sport in its infancy and continues to demonstrate its stranglehold on society.

The middle of the mountain is the scientific confusion surrounding CTE.

And the summit is cascading with red tape. Who is responsible? The leagues and organizations? The owners? The players? What will it take to make real change? How can we possibly remedy the loss of life that CTE has caused?

Then there are the curious cases of athletes like Holcomb, who suffer from depression and die, but are found not to have CTE. Should he be treated like a CTE victim while he’s alive? How do we draw a distinction between clinical depression and CTE-induced mental health struggles?

It’s a subject flooded with research, yet still so many questions. And until those questions are answered, athletes like Breen and Person will continue to come and go, defined by their unconfirmed yet confident diagnoses of CTE.

And most will go far too soon.