Here are the results of Round 4 of Gitcoin Grants quadratic funding:

The main distinction between round 3 and round 4 was that while round 3 had only one category, with mostly tech projects and a few outliers such as EthHub, in round 4 there were two separate categories, one with a $125,000 matching pool for tech projects, and the other with a $75,000

matching pool for “media” projects. Media could include documentation,

translation, community activities, news reporting, theoretically pretty much anything in that category.

And while the tech section went about largely without incident, in the new media section the results proved to be much more interesting than I could have possibly imagined, shedding a new light on deep questions in institutional design and political science.

Tech: quadratic funding worked great as usual

In the tech section, the main changes that we see compared to round 3 are (i) the rise of Tornado Cash and (ii) the decline in importance of eth2 clients and the rise of “utility applications” of various forms. Tornado Cash is a trustless smart contract-based Ethereum mixer. It became popular quickly in recent months, as the Ethereum community was swept by worries about the blockchain’s current low levels of privacy and wanted solutions. Tornado Cash amassed an incredible $31,200. If they continue receiving such an amount every two months then this would allow them to pay two people $7,800 per month each – meaning that the hoped-for milestone of seeing the first “quadratic freelancer” may have already been reached!

The other major winners included tools like Dappnode, a software package to help people run nodes, Sablier, a payment streaming service, and DefiZap.

The Gitcoin Sustainability Fund got over $13,000, conclusively resolving my complaint from last round that they were under-supported. All in all, valuable grants for valuable projects that provide services that the community genuinely needs.

We can see one major shift this round compared to the previous rounds. Whereas in previous rounds, the grants went largely to projects like eth2 clients that were already well-supported, this time the largest grants shifted toward having a different focus from the grants given by the Ethereum Foundation.

The EF has not given grants to tornado.cash, and generally limits its grants to application-specific tools, Uniswap being a notable exception. The Gitcoin Grants quadratic fund, on the other hand, is supporting DeFiZap, Sablier, and many other tools that are valuable to the community. This is arguably a positive development, as it allows Gitcoin Grants and the Ethereum Foundation to complement each other rather than focusing on the same things.

The one proposed change to the quadratic funding implementation for tech that I would favor is a user interface change, that makes it easier for users to commit funds for multiple rounds. This would increase the stability of contributions, thereby increasing the stability of projects’ income – very important if we want “quadratic freelancer” to actually be a viable job category!

Media: The First Quadratic Twitter Freelancer

Now, we get to the new media section. In the first few days of the round, the leading recipient of the grants was “@antiprosynth Twitter account activity”: an Ethereum community member who is very active on twitter promoting Ethereum and refuting misinformation from Bitcoin maximalists, asking for help from the Gitcoin QF crowd to…. fund his tweeting activities. At its peak, the projected matching going to @antiprosynth exceeded $20,000. This naturally proved to be controversial, with many criticizing this move and questioning whether or not a Twitter account is a legitimate public good:

On the surface, it does indeed seem like someone getting paid $20,000 for operating a Twitter account is ridiculous. But it’s worth digging in and questioning exactly what, if anything, is actually wrong with this outcome. After all, maybe this is what effective marketing in 2020 actually looks like, and it’s our expectations that need to adapt.

There are two main objections that I heard, and both lead to interesting criticisms of quadratic funding in its current implementation. First, there was criticism of overpayment. Twittering is a fairly “trivial” activity; it does not require that much work, lots of people do it for free, and it doesn’t provide nearly as much long-term value as something more substantive like EthHub or the Zero Knowledge Podcast. Hence, it feels wrong to pay a full-time salary for it.

Examples of @antiprosynth’s recent tweets

If we accept the metaphor of quadratic funding as being like a market for public goods, then one could simply extend the metaphor, and reply to the concern with the usual free-market argument. People voluntarily paid their own money to support @antiprosynth’s twitter activity, and that itself signals that it’s valuable. Why should we trust you with your mere words and protestations over a costly signal of real money on the table from dozens of people?

The most plausible answer is actually quite similar to one that you often hear in discussions about financial markets: markets can give skewed results when you can express an opinion in favor of something but cannot express an opinion against it. When short selling is not possible, financial markets are often much more inefficient, because instead of reflecting the average opinion on an asset’s true value, a market may instead reflect the

inflated expectations of an asset’s few rabid supporters. In this version of quadratic funding, there too is an asymmetry, as you can donate in support of a project but you cannot donate to oppose it. Might this be the root of the problem?

One can go further and ask, why might overpayment happen to this particular project, and not others? I have heard a common answer: twitter accounts already have a high exposure. A client development team like Nethermind does not gain much publicity through their work directly, so they need to separately market themselves, whereas a twitter account’s “work” is self-marketing by its very nature. Furthermore, the most prominent twitterers get quadratically more matching out of their exposure, amplifying their outsized advantage further – a problem I alluded to in my review of round 3.

Interestingly, in the case of vanilla quadratic voting there was an argument made by Glen Weyl for why economies-of-scale effects of traditional voting, such as Duverger’s law, don’t apply to quadratic voting: a project becoming more prominent increases the incentive to give it both positive and negative votes, so on net the effects cancel out. But notice once again, that this argument relies on negative votes being a possibility.

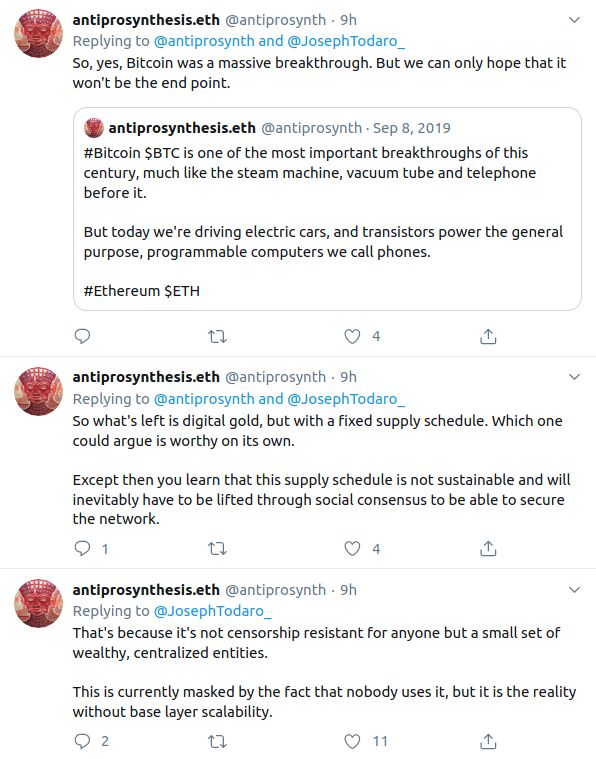

Good for the tribe, but is it good for the world?

The particular story of @antiprosynth had what is in my opinion a happy ending: over the next ten days, more contributions came in to other candidates, and @antiprosynth’s match reduced to $11,316, still a respectably high amount but on par with EthHub and below Week in Ethereum. However, even a quadratic matching grant of this size still raises to the next criticism: is twittering a public good or public bad anyway?

Traditionally, public goods of the type that Gitcoin Grants quadratic funding is trying to support were selected and funded by governments.

The motivation of @antiprosynth’s tweets is “aggregating Ethereum-related news, fighting information asymmetry and fine-tuning/signaling a consistent narrative for Ethereum (and ETH)”: essentially, fighting the good fight against anti-Ethereum misinformation by bitcoin maximalists.

And, lo and behold, governments too have a rich history of sponsoring social media participants to argue on their behalf. And it seems likely that most of these governments see themselves as “fighting the good fight against anti-[X] misinformation by [Y] {extremists, imperialists, totalitarians}”, just as the Ethereum community feels a need to fight the good fight against maximalist trolls.

From the inside view of each individual country (and

in our case the Ethereum community) organized social media participation seems to be a clear public good (ignoring the possibility of blowback

effects, which are real and important). But from the outside view of the entire world, it can be viewed as a zero-sum game.

This is actually a common pattern to see in politics, and indeed there are many instances of larger-scale coordination that are precisely intended to undermine smaller-scale coordination that is seen as “good for the tribe but bad for the world”: antitrust law, free trade agreements, state-level pre-emption of local zoning codes, anti-militarization agreements… the list goes on.

A broad environment where public subsidies are generally viewed suspiciously also does quite a good job of limiting many kinds of malign local coordination. But as public goods become more important, and we discover better and better ways for communities to coordinate on producing them, that strategy’s efficacy becomes more limited, and properly grappling with these discrepancies between what is good for the tribe and what is good for the world becomes more important.

That said, internet marketing and debate is not a zero-sum game, and there are plenty of ways to engage in internet marketing and debate that are good for the world. Internet debate in general serves to help the public learn what things are true, what things are not true, what causes to support, and what causes to oppose.

Some tactics are clearly not truth-favoring, but other tactics are quite truth-favoring. Some tactics are clearly offensive, but others are defensive. And in the ethereum community, there is widespread sentiment that there is not enough resources going into marketing of some kind, and I personally agree with this sentiment.

What kind of marketing is positive-sum (good for tribe and good for world) and what kind of marketing is zero-sum (good for tribe but bad for world) is another question, and one that’s worth the community debating. I naturally hope that the Ethereum community continues to value maintaining a moral high ground. Regarding the case of @antiprosynth himself, I cannot find any tactics that I would classify as bad-for-world, especially when compared to outright misinformation (“it’s impossible to run a full node”) that we often see used against Ethereum – but I am pro-Ethereum and hence biased, hence the need to be careful.

Universal mechanisms, particular goals

The story has another plot twist, which reveals yet another feature (or bug?) or quadratic funding. Quadratic funding was originally described as “Formal Rules for a Society Neutral among Communities”, the intention being to use it at a very large, potentially even global, scale. Anyone can participate as a project or as a participant, and projects that support public goods that are good for any “public” would be supported. In the case of Gitcoin Grants, however, the matching funds are coming from Ethereum organizations, and so there is an expectation that the system is there to support Ethereum projects.

But there is nothing in the rules of quadratic funding that privileges Ethereum projects and prevents, say, Ethereum Classic projects from seeking funding using the same platform! And, of course, this is exactly what happened:

So now the result is, $24 of funding from Ethereum organizations will be going toward supporting an Ethereum Classic promoter’s twitter activity. To give people outside of the crypto space a feeling for what this is like, imagine the USA holding a quadratic funding raise, using government funding to match donations, and the result is that some of the funding goes to someone explicitly planning to use the money to talk on Twitter about how great Russia is (or vice versa).

The matching funds are coming from Ethereum sources, and there’s an implied expectation that the funds should support Ethereum, but nothing actually prevents, or even discourages, non-Ethereum projects from organizing to get a share of the matched funds on the platform!

Solutions

There are two solutions to these problems. One is to modify the quadratic funding mechanism to support negative votes in addition to positive votes. The mathematical theory behind quadratic voting already implies that it is the “right thing” to do to allow such a possibility (every positive number has a negative square root as well as a positive square root).

On the other hand, there are social concerns that allowing for negative voting would cause more animosity and lead to other kinds of harms. After all, mob mentality is at its worst when it is against something rather than for something. Hence, it’s my view that it’s not certain that allowing negative contributions will work out well, but there is enough evidence that it might that it is definitely worth trying out in a future round.

The second solution is to use two separate mechanisms for identifying relative goodness of good projects and for screening out bad projects. For example, one could use a challenge mechanism followed by a majority ETH coin vote, or even at first just a centralized appointed board, to screen out bad projects, and then use quadratic funding as before to choose between good projects. This is less mathematically elegant, but it would solve the problem, and it would at the same time provide an opportunity to mix in a separate mechanism to ensure that chosen projects benefit Ethereum specifically.

But even if we adopt the first solution, defining boundaries for the quadratic funding itself may also be a good idea. There is intellectual

precedent for this. In Elinor Ostrom’s eight principles for governing the commons, defining clear boundaries about who has the right to access the commons is the first one. Without clear boundaries, Ostrom writes, “local

appropriators face the risk that any benefits they produce by their efforts will be reaped by others who have not contributed to those efforts.”

In the case of Gitcoin Grants quadratic funding, one possibility would be to set the maximum matching coefficient for any pair of users to be proportional to the geometric average of their ETH holdings, using that as a proxy for measuring membership in the Ethereum community (note that this avoids being plutocratic because 1000 users with 1 ETH each would have a maximum matching of ≈ k ∗ 500, 000 ETH, whereas 2 users with 500 ETH each would only have a maximum matching of k ∗ 1, 000 ETH).

Collusion

Another issue that came to the forefront this round was the issue of collusion. The math behind quadratic funding, which compensates for tragedies of the commons by magnifying individual contributions based on the total number and size of other contributions to the same project, only works if there is an actual tragedy of the commons limiting natural donations to the project. If there is a “quid pro quo”, where people get something individually in exchange for their contributions, the mechanism can easily over-compensate.

The long-run solution to this is something like MACI, a cryptographic system that ensures that contributors have no way to prove their contributions to third parties, so any such collusion would

have to be done by honor system. In the short run, however, the rules and enforcement has not yet been set, and this has led to vigorous debate about what kinds of quid pro quo are legitimate:

[Update 2020.01.29: the above was ultimately a result of a miscommunication from Gitcoin; a member of the Gitcoin team had okayed Richard Burton’s proposal to give rewards to donors without realizing the implications.

So Richard himself is blameless here; though the broader point that we underestimated the need for explicit guidance about what kinds of quid pro quos are acceptable is very much real.]

Currently, the position is that quid pro quos are disallowed, though there is a more nuanced feeling that informal social quid pro quos (“thank yous” of different forms) are okay, whereas formal and especially monetary or product rewards are a no-no. This seems like a reasonable approach, though it does put Gitcoin further into the uncomfortable position of being a central arbiter, compromising credible neutrality somewhat.

One positive byproduct of this whole discussion is that it has led to much more awareness in the Ethereum community of what actually is a public good (as opposed to a “private good” or a “club good”), and more generally brought public goods much further into the public discourse.

Conclusions

Whereas round 3 was the first round with enough participants to have any kind of interesting effects, round 4 felt like a true “coming-out party” for the cause of decentralized public goods funding. The round attracted a large amount of attention from the community, and even from outside actors such as the Bitcoin community. It is part of a broader trend in the last few months where public goods funding has become a dominant part of the crypto community discourse. Along with this, we have also seen much more discussion of strategies about long-term sources of funding for quadratic matching pools of larger sizes.

Discussions about funding will be important going forward: donations from large Ethereum organizations are enough to sustain quadratic matching at its current scale, but not enough to allow it to grow much

further, to the point where we can have hundreds of quadratic freelancers instead of about five. At those scales, sources of funding for Ethereum public goods must rely on network effect lockin to some extent, or else they will have little more staying power than individual donations, but there are strong reasons not to embed these funding sources too deeply into Ethereum (eg. into the protocol itself, a la the recent BCH proposal), to avoid risking the protocol’s neutrality.

Approaches based on capturing transaction fees at layer 2 are surprisingly viable: currently, there are about $50,000-100,000 per day (~$18-35m per year) of transaction fees happening on Ethereum, roughly equal to the entire budget of the Ethereum Foundation. And there is evidence that miner-extractable value is even higher. There are all discussions that we need to have, and challenges that we need to address, if we want the Ethereum community to be a leader in implementing decentralized, credibly neutral and market-based solutions to public goods funding challenges.

Originally published as “Review of Gitcoin Quadratic Funding Round 4” with the WTFPL license