The Covid-19 pandemic has shaken up businesses across the world like never before. Like their global peers, Indian startups are also realigning their strategies to adjust to the new normal. But more than the disease, the ongoing Sino-Indian tensions, triggered by a border standoff, could put India’s fast-growing startup ecosystem in a spot.

Mega funding rounds from Chinese investors could be a thing of the past after the changes in the foreign direct investment (FDI) norms and the pre-clearance mandates regarding Chinese investments came into effect in April 2020. A steady rise in anti-China sentiment due to border clashes and the government’s ban on 220 Chinese apps further worsened the situation. China has also faced a backlash from other countries, including the US, for not curbing the spread of the pandemic that reportedly started there.

Although a sharp drop in the startup funding inflow from Chinese investors is not unlikely – the Ant Group from the stable of Alibaba even mentioned it in its IPO prospectus at the Hong Kong stock exchange – there is another side of the coin. As the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology banned 59 Chinese-owned applications in June and 118 apps in September, and a total of 220 apps until now, ‘made-in-India’ apps are taking advantage of the ban and catering to a fast-growing Indian audience.

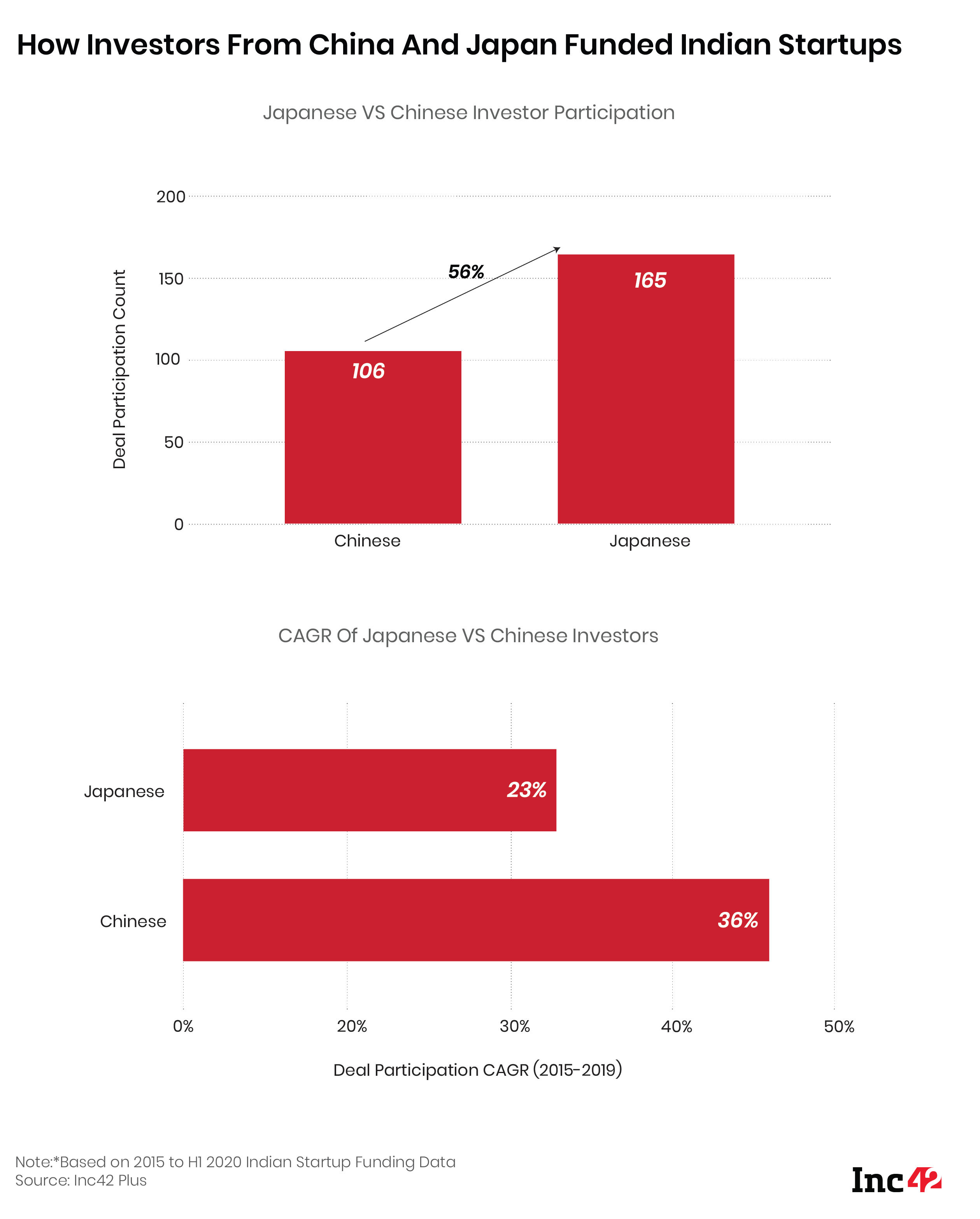

There could be a shift in funding sources, too, leaving the field wide open for non-Chinese investors. The latter would want to come in, given the India market size and the plethora of opportunities. As we do a recap of the year, we take a deep dive into the opportunities, repercussions, short-term issues and long-term changes that will impact Indian startups’ financial playbook.

Ban On Chinese Apps Opens The Market For Made-In-India Alternatives

Even though TikTok lovers and contributors were disappointed after the sudden ban, the government’s move was welcomed by many entrepreneurs. The ban means Indian startups in the gaming and short video app space need not compete with TikTok, SHAREit, Helo and others with a stronger tech play and better capital inflow.

To understand the reach of TikTok in India, let us take a look at the numbers. According to mobile and data analytics firm App Annie, Indians spent 900 Mn and 5.5 Bn hours on TikTok in 2018 and 2019, respectively. The number of monthly active users (MAUs) also increased by 90% to 81 Mn as of December 2019 compared to the same period in the previous year. This data covers Android users and shows the huge opportunity homegrown apps can leverage now that TikTok has left.

As the forced withdrawal of TikTok and the likes left a huge vacuum, made-in-India short video apps such as Chingari, Roposo, Mitron, Bolo Indya, Trell and MX TakaTak quickly jumped in to fill the gap.

Almost overnight, Indians viewers had found suitable alternatives, and the results were evident. Within a day, Chingari’s viewership nearly doubled to 370K users per minute from 187K. Similarly, regional social media platform Sharechat’s Moj app, which was launched right after the ban, saw more than 10 Mn downloads in less than a week. Mitron, another app in this domain, saw 5 Mn-plus downloads within a month of its launch, and more than 500K downloads in a single day.

“It was high time to bring Indian app developers in the limelight. Most of the Chinese apps banned by the government are vanity apps and do not impact the Indian economy in the same manner it would affect China. “If they (Indian startups) can provide good substitutes with a strong tech backbone, deliver the right UX in sync with the Indian mindset and market these apps well, they can rewrite the entire ‘Make in India’ and ‘Digital India’ campaigns,” says Ankur Bansal, cofounder and director of BlackSoil, a venture debt firm.

India’s Gaming Startups Get Ready To Play

The ban not only got the ball rolling for short video apps. It was an excellent opportunity for India’s gaming startups to beat ‘Brand PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG)’ and its most popular games. In September, the gaming app was banned, wiping off two most popular titles – Clash of Kings (50 Mn-plus downloads and 4.1 rating on Google Play Store) and Mobile of Legends (100 Mn-plus downloads and a rating of 4.2).

The micro-transactions for in-app purchases and subscriptions for monthly rewards made PUBG Mobile one of the top-grossing mobile games in India. A year after its India launch in 2018, it started clocking an average monthly revenue of $7-8 Mn.

Once again, the numbers show it is time for Indian gaming apps to cash in on the opportunity. The Indian alternative that gained the most traction in this space was Fearless And United Guards (FAUG). The PUBG rival saw the number of pre-registrations cross the 1 Mn mark within 24 hours.

The ban has also stretched the space for esports startups such as Nodwin Gaming, Ewar Games, Gaming Monk and other games and genres such as Call of Duty (COD) Mobile, Free Fire and Fortnite. “It is time we start building and supporting our video-games ecosystem, which is built on our culture and ethos. This is a great opportunity for homegrown apps to encash their presence,” says Lokesh Suji, director of Esports Federation of India.

Besides the ban, the rising demand for personal entertainment during Covid-19 lockdowns also led to better discoverability of Indian products.

“Because of the ban, a lot of new and established players took the plunge and created similar products to fill the huge void,” says Paavan Nanda, cofounder of the gaming startup, WinZo.

Apart from entertainment and social media, several other domains such as ecommerce, file-sharing, productivity tools and news aggregation may also benefit from the turn of events. Indian alternatives such as Kaagaz Scanner and Doc Scanner are likely to thrive now as a slew of productivity apps, including CamScanner, ES File Explorer and Baidu Translate, among others, have been banned as well.

Investors are not lagging, either. In November this year, Kaagaz Scanner raised $575K in seed funding, led by Pravega Ventures.

The Impact Of Ban On Startup Funding

The ban may spell a bigger opportunity and longer runway for homegrown players. Still concerns over startup funding cannot be ignored as the standoff between the two Asian giants continues. As mentioned before, the sparring shifted to the trade front as early as April when the Indian government amended the extant FDI policy for curbing opportunistic takeovers or acquisitions of Indian companies due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. It was also noted that China-backed funds were seeking to grab companies suffering a valuation slump due to Covid’s impact.

“The Covid-19 crisis has unsettled India’s startup and investor communities alike. The decision (to change FDI norms) could have waited, considering many startups are in dire need of early-stage funding. The latest move will create an additional barrier between them and foreign investors,” said Dr Apoorv Ranjan Sharma, cofounder and managing director of 9Unicorn, in an interview in April 2020.

Two months later, the ban on the first lot of Chinese apps came as India saw a nationwide rise in anti-China sentiment. The trend has continued ever since and may stunt the growth of many startups. If Chinese investors decide to retaliate, the capital freeze is likely to leave a huge funding gap for many startups which are already struggling to cope with a pandemic-hit economy. For unicorns, however, this came as a big blow immediately. Alibaba and Tencent, two of the most prominent Chinese investors in India, have stakes in several Indian unicorns such as Paytm, Zomato, BigBasket, Flipkart, BYJU’S, Hike and MX Player.

Funding Hunt Moves Beyond China Now

For many entrepreneurs, funding is not the only issue. Many of them think Chinese investors have brought in a lot of experience and learning for Indian startups when it comes to making products for the domestic market. However, people realised that the border issues would not be resolved soon and started making changes in their fundraising plans.

“Everybody has made alternative funding plans. I would say the smartest company to do it is Jio Platforms. It started the trend of non-Chinese funding and boosted others’ confidence,” says Anup Jain, managing partner at Orios Venture Partners.

According to Jain, Jio’s approach has changed the general mindset, and people are now looking at the US, Europe, the Middle East and other countries. “Many other large funds which were cautiously looking at India, especially those who were sitting on the fence, are now more open to investing in Indian startups,” he adds.

Jain also claims that he and other fund managers see many queries and a lot of interest from different parts of the world (other than China) as investors want to participate in private- and public-sector funding.

For instance, Singapore-based wealth fund GIC (Government of Singapore Investment Corporation) is planning to set up a $2-3 Bn India-focussed public market fund. Masayoshi Son-led Japanese conglomerate SoftBank also remains a key investor in the India startup ecosystem even though its portfolio companies have failed to deliver in phase 1.

The company’s Vision Fund 2 (SVF2) will focus on enterprise, healthtech and SaaS segments and is reportedly ready to make its first SaaS investment in India by infusing $80-100 Mn in Pune-based startup MindTickle. Indian eyewear startup Lenskart was the first company to receive funds from SVF2 in December 2019.

According to media reports, the first vision fund has already invested more than $10 Bn in Indian startups. Both funds are now looking to invest in secondary deals (wherein a new investor buys out early-stage funders) in India. This may not be great news for growth-stage companies, but SoftBank’s recent funding is proof enough that the company has not entirely discarded its earlier India strategy.

New York-based hedge fund Tiger Global is also back in the fray now that Chinese investors are on the backfoot and SoftBank seems to have grown somewhat risk-averse. Its most recent investment (reportedly in the range of $75-100 Mn) in Unacademy came in November 2020, valuing the K-12 edtech company at $2 Bn.

“There is no shortage of funds in India. There is a certain growth potential here, and investors would put their money in this country. In the past six months, we have seen a huge inflow of tech FDI coming to Reliance Jio, and that proves the point,” says Amit Bhandari, author at Gateway House, a council that engages Indian businesses and opinion leaders in dialogues on foreign policy issues.

Jain concurs, saying that unicorns like Razorpay, Zerodha, Zomato and a few others are already looking beyond China for funding. For example, Zomato has recently raised $62 Mn from Singapore-based state investment arm Temasek after the company’s plans to get funding from the Ant Group, an affiliate of Alibaba Group Holding, got delayed.

“I do not see any difficulty for Indian startups to access funding. There is an interest to participate in the Indian tech sector from other parts of the world like the Middle East, Japan and Europe,” sums up Jain of Orios Venture Partners.