The ripples of the Charlie Hebdo attack spread far.

It wasn’t just the sense of nervousness about terrorism, but also about something very profound.

About two questions that still trouble the country.

The first is to ask why the Kouachi brothers and Amedy Coulibaly, all of them born in or around Paris, had ended up being radicalised into committing such grotesque acts of violence.

How had they slipped through the net, despite the fact that one of the trio – Cherif Kouachi – had once been arrested as he was about to leave for Syria, on a self-proclaimed mission to fight American troops in Iraq.

At that time, Cherif Kouachi is reported to have cut a rather bizarre, deluded figure – angry but also naive and immature.

But the prison sentence he was given was the catalyst for his transformation into a future terrorist.

The uncomfortable truth for the French security services is that we now know exactly where the radicalisation of these three killers began.

It happened in prison, under the watch of French authorities.

It was there, behind the towering walls of Fleury-Merogis prison that Cherif Kouachi met Djamel Baghal, jailed for plotting to bomb the US embassy in Paris, and Amedy Coulibaly, a bank robber.

Coulibaly had converted to a radical form of Islam; Kouachi would follow.

The two, along with Cherif Kouachi’s brother Said, would carry out the co-ordinated attacks at Charlie Hebdo and at the Hypercacher kosher supermarket in January 2015.

This is not about attackers coming from a distant land.

The Charlie Hebdo attacks, and the ones that have followed, often involve people with strong links to France, but who feel a sense of hatred towards the land.

And there is little doubt that the radicalisation that has happened, and is still happening, in French prisons has exacerbated the problem.

Which brings us to the second question, about how the French deal with a fundamental question.

France prides itself on being a secular nation, where state and religion are separate.

The right to blaspheme is cherished as a tenet of free speech.

That’s why President Macron has defended freedom of expression.

But now, something as ephemeral as a cartoon was being blamed for the deaths of so many people.

Was a caricature worth such pain?

Almost six years later, Maryse Wolinski is still angry about her husband’s death.

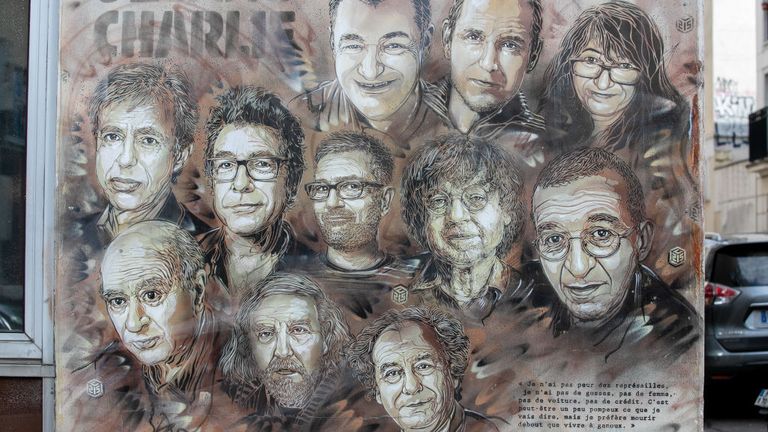

George Wolinski was a renowned cartoonist, who was 80 years old when he was shot dead at Charlie Hebdo.

To this day, his widow has 24-hour police protection – we’re not allowed to say where she lives.

“Yes, I’m scared, but I try not to think about it,” she tells me.

I ask her that question, about whether the freedom to publish cartoons was worth the pain and death that had followed.

She bristles, irritated that the question could even be asked.

“It is not for France to change its laws or its way of life. Those who do not agree with this way of life, or with these laws – should leave the country.

“They killed my husband, my love, but they didn’t kill his ideas. It is often said that ‘yes I agree with the cartoons but…’ This ‘yes, but’ is cowardly. We have the right to blaspheme, and the freedom to think.”

But this right to blaspheme continues to cause ructions.

When this trial began, Charlie Hebdo republished the controversial cartoons.

As an illustration of the divisive nature of such an action – it was followed by applause within French Parliament – it prompted a violent attack on two people who were standing outside the office building where the original 2015 attack happened.

The attacker thought they were staff from Charlie Hebdo; in fact the magazine had long since moved out.

The beheading of teacher Samuel Paty was linked to the caricatures, too.

So as long as France cherishes – perhaps even prizes – acts of controversial free speech, so it will be at odds with some of its citizens.

According to the French government, the country is home to more than four million Muslims, and this fracture between those who see the caricatures as a totem of free speech, and those who see them as grotesquely insulting and wantonly offensive, is not hard to spot.

Patrick Pelloux is a doctor who works in hospital accident and emergency departments.

He was an occasional contributor to Charlie Hebdo and, on the morning of the attack, had a meeting just round the corner from the offices.

Alerted to what had happened, he was the first person on the scene – before the police or ambulance crews had arrived.

“The brutality, the violence…it has no words,” he told me.

“If you want to shoot in a room that is very small, about 15 square metres, with a Kalashnikov, that is terrible. They were the wounds from weapons of war.

“There is a war being played out in France. There is a real problem with Islamo-fascism and there are going to be more attacks. They are very organised. There will be an attack in Paris, you will see.”

It is a brutal vision of the future, and there will be those who consider it too bleak.

When I spoke to Imam Kemadou Gassama, a cleric at one of the city’s mosques, he told me that those who killed in the name of Islam “have nothing to do with our religion”.

He said the caricatures “had hurt…but that doesn’t give us the right to kill someone”.

And yet the tension remains.

President Macron has made clear that free speech is fundamental to his vision of France; leaders from majority-Muslim nations have castigated him for alleged Islamophobia.

Turkey’s President Erdogan suggested he was mentally unstable.

France has made efforts to counter radicalism in its schools, mosques and prisons, but it’s hard to say if it has had much impact.

Nearly six years after the Charlie Hebdo attack, the same questions are being asked, the same fears and tension and the same nerves are frayed.